Pop Beloved: Revisiting the Reivers

By Michael Bertin. Austin Chronicle, April 26, 2002.

Nineteen eighty-five. What was on the radio in 1985? Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants to Rule the World,” REO Speedwagon’s “Can’t Fight This Feeling,” a-ha’s “Take On Me,” and who could forget Billy Ocean’s “Loverboy”? (Please God, help us forget.) Of course, “We Are the World” was all the rage that year, and Madonna, well, she was fast becoming MTV’s favorite Pop Tart.

Also released that year on Atlanta-based indie dB Records was a record (yes, vinyl) titled Translate Slowly by Austin’s Zeitgeist. It was a collection of guitar-pop songs that was both buoyant and sobering, endearing in its innocence and exuberance. Quick, which sold more copies, Translate Slowly or Like a Virgin? Okay, it’s a stupid question. Really stupid. But Zeitgeist, which later changed its name to the Reivers, wasn’t just a future footnote in local music scene history. They were a beloved band that signed to Capitol Records and cut two LPs for the home of the Beatles after their dB debut.

Also released that year on Atlanta-based indie dB Records was a record (yes, vinyl) titled Translate Slowly by Austin’s Zeitgeist. It was a collection of guitar-pop songs that was both buoyant and sobering, endearing in its innocence and exuberance. Quick, which sold more copies, Translate Slowly or Like a Virgin? Okay, it’s a stupid question. Really stupid. But Zeitgeist, which later changed its name to the Reivers, wasn’t just a future footnote in local music scene history. They were a beloved band that signed to Capitol Records and cut two LPs for the home of the Beatles after their dB debut.

Listening to those two LPs today, newly reissued on Nashville’s Dualtone Records — 1987’s Saturday and its follow-up two years later, End of the Day — they sound very much of the time, albeit somewhat dated. Many of the songs are part and parcel of the nascent “alternative” music from the era, which moved to the mainstream bands like R.E.M. and 10,000 Maniacs. Many of the songs hold up quite well, in fact. Why didn’t the Reivers (aka Formerly Zeitgeist) sell as many records as the Material Girl, or at least a respectable denominator thereof?

In the early- to mid-Eighties, Austin was simply a different place. Sure, an economic boom had just gone bust, much like now, but open an old Chronicle and look at the venue listings. Club Foot, where R.E.M. once opened for Houston’s the Judys, is now a parking lot. Soap Creek Saloon? Subsumed in Bee Caves development. The Continental Club existed in its same spot under its same name, but back then, it was run by Liberty Lunch proprietor Mark Pratz and was a much danker and dirtier place. For its brief existence, Sparky’s was underground even by underground standards. The Crown & Anchor was a place called the Beach where you could pay $5 to see the Butthole Surfers play.

Locally, pop music was everywhere. Austin’s punk heyday had passed, but the burgeoning music scene was still quite vibrant circa 1985. The True Believers’ three-guitar roots blast had been tapped to take the scene national, while the Wild Seeds were on the verge of spawning a mild FM hit with “I’m Sorry I Can’t Rock You All Night Long.” Joe King Carrasco, a couple years removed from Synapse Gap and Party Weekend — two de rigueur Tex-Mex beach punk records if ever there were a thing — was starting to develop a national profile.

Along with Minneapolis and Athens, Ga., Austin was it for what was then called “college music” — what’s now more or less encompassed by the term “indie rock.” MTV’s I.R.S. Records-produced The Cutting Edge even documented the scene for the rest of the country; Glass Eye, Doctors’ Mob, Daniel Johnston. Front and center were Zeitgeist, the poster kids of Austin’s “New Sincerity” movement, as the scene had been dubbed by the Skunks’ Jesse Sublett.

Looking at that roll call of acts now, boomers and neophytes alike are probably thinking, “I’ve heard of Daniel Johnston, but who the hell are the others?” That’s one byproduct of a city where natives are treated with a curiosity befitting circus freaks. History has a tendency to be ephemeral, but what those bands have in common is that, for all the hype, buzz, and promise, none of them ever “made it.”

Austin, Athens, and Minneapolis might have been the trinity of cool, but at least Athens produced R.E.M. and the B-52s, and Minneapolis gave us Soul Asylum, Hüsker Dü, and the Replacements. What happened here? Michael Hall of the Wild Seeds admits that it was something of a running joke that Austin was thought cursed by the local music community when it came to breaking bands nationally.

“We all thought the True Believers were going to be the next T. Rex,” sighs Hall. “They had everything — the attitude, the look, the songs, the three guitars. We all thought they were going to be huge. And the Reivers, too. They were like X. They had the boy-girl thing, the songs, they were on a good label. I don’t know. I hate to even joke that we weren’t that good, but maybe that’s the case.”

——————————————————————————–

Saturday

In the summer of 1983, John Croslin, best known these days for his production work for the likes of Spoon, the Damnations, and Guided by Voices, hooked up with University of Texas Music major and Bay Area transplant Kim Longacre. The two knew each other thanks to Longacre’s boyfriend managing Croslin’s band the Make. Sharing singing and guitar duties, the pair hooked up with Kelly Bell and Joey Sheffield (later of Fastball), soon replaced by Cindy Toth and Garrett Williams on bass and drums respectively. Zeitgeist had hatched.

Within a relatively short time, the local quartet had saved enough money to finance a 7-inch single. Remember, compact discs were infant, nay, embryonic, technology at this point, so a self-financed 45 was still an accomplishment for any local band.

We glued the sleeves together ourselves,” laughs Longacre. “It was a total cottage industry. I remember they were even kind of warped and we had to put stacks of books on them.”

We glued the sleeves together ourselves,” laughs Longacre. “It was a total cottage industry. I remember they were even kind of warped and we had to put stacks of books on them.”

That’s a marked contrast from today where a musician with minimal tech skills, a free copy of ProTools, and a CD burner can engineer and manufacture his own product on a home computer for pennies apiece. Despite the modest beginnings, “Freight Train Rain” b/w “Electra” gave the band its first substantial break. Through a friend of a friend, Danny Beard had gotten ahold of the record and took a liking to it. Beard ran dB and helped nurture such acts as the Swimming Pool Qs, the B-52s, Matthew Sweet, Fetchin’ Bones, and Guadalcanal Diary.

“What’s funny about associating things with Danny Beard is that the show I remember he saw us was one of the worst shows we ever played,” notes Croslin of a show Zeitgeist played in Atlanta. “We had gotten in a car wreck earlier that day, and we played at this ex-strip club. Basically, we were playing on the runway where they danced, right in front of this glass wall about five feet away from us. So everyone gathered around the sides as if they were watching a stripper dance. I just remember it being one of the worst shows. But Danny loved it and wanted to sign us.”

That not only led to Translate Slowly, but also to Zeitgeist getting signed to Capitol, albeit not without a few hiccups, including a pregnancy for Longacre that caused her to depart the band temporarily. Capitol had something akin to a first-look deal with Beard and dB. It’s a bit of an oversimplification, as Croslin notes, but basically, Capitol looked and decided to sign Fetchin’ Bones and Zeitgeist at the same time.

At that point, it seemed as though Zeitgeist had everything going for it: a damn fine record under its belt, credibility from a respected indie label, and a fervent following in its hometown, as well as pockets of support in major cities like Washington, D.C., and Chicago. Best of all, college music was becoming commercially viable. On top of all that, the band’s Capitol debut was being produced by Don Dixon, who by virtue of his work with R.E.M. and the Smithereens, was in demand. The proverbial planets had aligned for Zeitgeist.

So they recorded two albums for Capitol. Two buoyant, endearing, and critically well-received albums. Albums that went nowhere. I believe “stiffed” is the proper industry terminology. What happened? Well, nothing happened to Zeitgeist. And that’s actually where some of the problems may have started. You see, there was this chamber ensemble based out of Minnesota called Zeitgeist, and try as they might, Capitol Records couldn’t negotiate them out of their rights to the name.

“I can’t remember what their exact demands were,” claims drummer Garrett Williams, “but they were just a little bit more than not only Capitol, but what we were willing to do. I think they wanted us to put ‘AT’ on the beginning of the name — for Austin, Texas — or something silly like that. Basically they wanted to boot us from the end of the alphabet to the beginning.”

On the eve of Saturday’s release, Zeitgeist was forced to change its name. A band vote produced the Reivers, after the William Faulkner book, so it’s at this point that the story of Zeitgeist becomes that of the Reivers. While Williams thinks the change set the band back “quite a bit,” Croslin downplays its significance.

“It hurt us some, but I don’t think it was a death blow,” he offers. “One of the things that was a drag was that we kept having to explain it to everyone. It was the question everyone would start with. It got really tiring.”

In fact, locally, it was joked that the band was as well known as Formerly Zeitgeist as it was the Reivers, but the band’s misfortunes actually began prior to the name change. During the recording of Saturday — and stop me if you’ve heard this one before — the band’s A&R guy left Capitol. Initially, when the Reivers ended up with a new A&R rep in Tom Whalley, who would go on to become insanely successful in turning Interscope Records into an industry behemoth, things didn’t look so bad. All right, so Whalley was working with Poison. He was also working with Crowded House.

“We heard Crowded House and we thought, ‘Okay, this guy understands,'” recalls Croslin. “But he was really coming from a more standard record company point of view, and we weren’t that. We didn’t always play great, and we didn’t look like rock stars. They didn’t know how to deal with that I think.”

Capitol sent “Secretariat” to radio as the first single. A driving combination of rhythm and muscular precision tempered with insouciant male-female harmonies, the song garnered only pockets of airplay — KLBJ locally, WXRT in Chicago, etc. — with the band seemingly getting the short end of the major-label stick.

Capitol sent “Secretariat” to radio as the first single. A driving combination of rhythm and muscular precision tempered with insouciant male-female harmonies, the song garnered only pockets of airplay — KLBJ locally, WXRT in Chicago, etc. — with the band seemingly getting the short end of the major-label stick.

“It was really frustrating,” says Longacre. “We felt like everyone was really into it when talking to them, but nothing would happen. We didn’t know what to think. It was a perplexing situation. I’m sure if we had somebody in Los Angeles who was enthusiastic about us things might have been handled differently, but we didn’t. That’s not unusual. If we had had a major hit, I’m sure things would have been different too.”

When it came time to record a follow-up, it was obvious to the band that the level of enthusiasm at Capitol had definitely waned. So much so that when it came time to do the legwork for End of the Day, some of what any band should expect a label to do for them ended up falling to the Reivers themselves. It was the four band members, for instance, who divvied up the list of promotions people in all 50 states and made calls to make sure that records were in stores and posters were on walls. What’s the point of signing to a major label if you have to do your own Mickey Mouse promotion work yourself?

“We didn’t go into it saying there is no way this record is going to do anything” avers Williams. “We went into it wanting to make the best record, wanting to go out and support it and get some sales going. We were hoping it would work out. We felt like if we got some amount of success going with it, Capitol would follow along, but we didn’t really feel like they were going to start it themselves.”

Croslin, on the other hand, is almost apologetic for the label.

“A lot of people at Capitol were behind us and really worked hard,” he maintains. “It just didn’t happen. I don’t feel good about pointing the finger and saying, ‘Here’s what they did wrong,’ because I don’t know what that is. I don’t know that they had a lot to work with.”

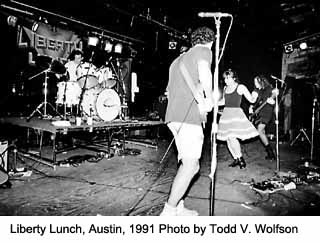

When it was released in 1989, End of the Day hardly made a splash worthy of the label’s attention. The band did record some demos for what would become Pop Beloved, but Capitol wasn’t sufficiently impressed, and the band was dropped. Pop Beloved, the band’s last record, was released on dB in 1991. Shortly thereafter, the Reivers were no more. Croslin went to the band and said he needed to take a break. Longacre recalls, “Within two days we realized this isn’t a break. This is breaking up.”

——————————————————————————–

End of the Day

A decade later, Croslin and Toth are still in the music industry to varying degrees. Croslin is a respected, sought-after engineer and producer. Toth, meanwhile, played with local space-rock precursors the Flying Saucers for a few years, and was most recently in a band called Trigger Happy. Williams now works in the computer industry. Longacre still does some singing, but is mostly busy being a mom.

Still, the question remains: Why didn’t the Reivers achieve commercial success? Again, the late Eighties were vibrant with college radio. R.E.M., U2, and 10,000 Maniacs were becoming mainstream bands, huge ones at that. MTV’s 120 Minutes was one of the network’s most popular programs. Hell, even Robyn Hitchcock was getting played on commercial FM radio. So the Reivers’ A&R guy left, big deal, the planets were aligned fer crying out loud.

“That’s why Capitol signed us in the first place,” insists Longacre. “I think they were like, ‘Oh man, we’ve got to get in on this.’ But they had no expertise at that point. They didn’t know how to market it. And maybe it was a timing thing for us. Had we come along a few years later, it might have been a completely different story.”

The last point is worth conceding. A few indie bands had broken through in 1987, but still a few years away was the revolution Nirvana touched off. It was the Seattle trio’s wholesale reinvention of popular music that opened things up not only for grunge bands, but also for those long-languishing pop bands that were fringe Eighties acts because they: a) weren’t Michael Jackson, b) didn’t play synthesizers, and c) had neither big hair nor Charvel guitars. And yet in 1985, U2 won Best Band honors in both Rolling Stone’s critics and readers polls. So the environment wasn’t completely hostile toward bands without power ballads.

Alejandro Escovedo, who played in Austin’s other next big hope of the time, the True Believers — the Rolling Stones to the Reivers’ Beatles (or Oasis to their Blur if you’re under 30) — doesn’t see the failure of Austin bands to achieve mainstream success as a failure at all.

Alejandro Escovedo, who played in Austin’s other next big hope of the time, the True Believers — the Rolling Stones to the Reivers’ Beatles (or Oasis to their Blur if you’re under 30) — doesn’t see the failure of Austin bands to achieve mainstream success as a failure at all.

“How many records did the Replacements really sell?” he asks. “Were they a megaband? I don’t think so. Yet they influenced a lot of bands, and if you look back, I’m sure the Wild Seeds influenced as many bands. So did the True Believers, and so did the Reivers. I’ve always hated this concept that Austin was an unsuccessful town because it never produced a Hüsker Dü. In my opinion, we were better off because of it.”

Maybe the Reivers didn’t make a noticeable impact for the same reason that 9.9 out of 10 bands don’t: They just didn’t catch on. Guadalcanal Diary, another dB band that got signed to a major (Elektra), also put out four good records (okay, three good — produced incidentally by Don Dixon — one barely decent), and ended up with a similar fate as that of the Reivers. The Call also had a couple of good albums, one for Mercury and one for Elektra, and more importantly, fairly good airplay support on multiple singles. It didn’t keep them from a similar end. The Hoodoo Gurus, same thing. The list is long.

“It’s funny,” admits Croslin, “because for me, it’s a lot more to me than just, ‘Could the Reivers sell?’ I have a lot of insecurities about my musicianship and my songwriting, so part of me says, ‘Of course. Yeah. I suck.’ But part of me says, ‘We were a great band, and moved people somehow.’ We did well here in Austin, and we did well when we went touring. A lot of people liked us. Whether that could have become a bigger seller, I don’t know.”

Nevertheless, the Reivers albums weren’t without fans, and the band can take small consolation in knowing they were influential to some. In the liner notes of the reissue of End of the Day, former Austin music scribe and No Depression founder Peter Blackstock writes about how he once gave the Reivers T-shirt off his back to Ryan Adams when Kid Country Rock raved about how much of a fan he was. Then there’s Hootie & the Blowfish, who took to covering the Reivers’ “Araby” onstage and put a cover of it and “Almost Home” on the band’s collection of rarities and B-sides.

Okay, Hootie as your biggest pimp is a mixed blessing, but hell, they sold over 15 million albums. Croslin and his former bandmates, however, shirk off any lasting influence or importance the band might have had. In fact, two weeks after Longacre had gotten her copies of the reissues, she still hadn’t listened to them. Williams only hears them when someone else in the family puts them on. And when he does, he has mixed feelings.

“Some of it I say, ‘I can’t believe we let that go out like that.’ Other things I listen to and go, ‘That’s as good as anything on the radio.'”

“I have trouble listening to them now,” confesses Croslin, “and I feel bad saying that, because I think the Reivers were a great band, and I think those records are cool, but there’s so much I don’t like about them — songwriting-wise and production-wise.”

Ultimately, though, the Reivers were important and successful for the reason any band would be — commercial windfall or none.

“We had a great time, and we meant something to a lot people,” admits Croslin. “When we were on, we really communed with the audience well. It was exciting, and it was a great experience.”